- Joined

- Oct 12, 2005

- Posts

- 227

- Likes

- 158

Here's the 3rd part of the educational series: What’s the best way to test and compare in-ear monitors? Just like last week, this segment comes via the UE University but is posted in its entirety here.

We’ve been talking about various ways to test in-ear monitors. We started off by discussing the benefits of using pure tones and then we moved on to analyzing overtones and harmonics of single instruments. Today, we’re going to put it all together and talk about the mix. In doing so, we’re also going to talk about the history of in-ear monitors and how their use on stage differs from their use for audiophiles.

Audiophiles want to hear a final track as it was mixed and mastered. Audiophiles want to hear every nuance of the recording. But this is the realm of studio work and in-ear monitors were initially invented/ developed for stage use. In-ears were made to monitor live performances and live music is a totally different animal than the studio. Think about that for a second. The needs of a performing musician trying to hear themselves while onstage are totally different than an audiophile wanting to hear the best representation of a studio recording.

The mix:

On stage, a musician rarely wants to hear a full mix. They often just want to hear themselves and how their parts fit into the whole. That’s what in-ears are really about—giving artists the ability to hear themselves over the stage noise. Singers want to hear a vocal mix. Drummers want a rhythm mix. Guitarists want to hear the guitars and bass players want the bass.

When auditioning in-ears, it is critical to keep all this in mind. You have to realize that listening to a monitor mix is very different than listening to a front of house mix — which is what the audience hears. A front of house mix is the sum of all the parts. A monitor mix is just a part.

But what part?

Exactly! And herein is the key to unlock all in-ear monitor riddles. This is the lens to look through when comparing any and all monitors in the future. As a manufacturer, we have no idea what part of the mix a musician will be listening to. A UE-18 needs to be able to work for a vocalist, a drummer, a bass player, a guitarist, and an engineer. It needs to be able to handle a front of house mix but it also needs to excel with just vocals. This is why the crossover networks are so important and why I had stressed listening to each individual frequency in the prior articles. Every monitor needs to be able to do everything. Think of it like hiring a baseball player who is amazing in every position. No matter what, you’re covered.

Now, add to this equation that sound is subjective and based on preference. And remember, we’re still talking about live performances. It’s as simple as realizing that some drummers want a huge bottom-end while others prefer to focus on their cymbal work. Remember that next time you are comparing various models and when you’re searching for the sound signature that is right for you. Don’t settle for a sound signature that doesn’t do everything you want it to do. Move on and audition another model. That’s the beauty of choice.

Back to the mix:

OK. So wrapping it all up. You know that sound is subjective. You know that different models cater to different preferences. And you know that musicians listen to different mixes than the audience and the studio recordings.

These facts are liberating. They give you the freedom to never settle and they encourage you to find that perfect sound that just simply fits.

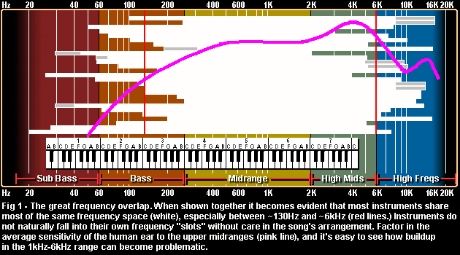

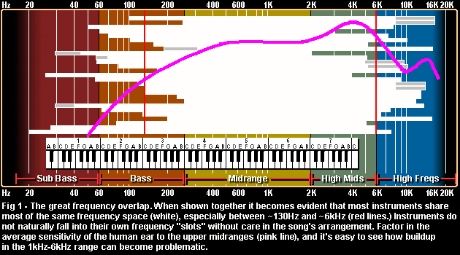

Before I leave you to go and seek out your sound signature, there is one last technical bit to pay attention to. If you look at the Great Frequency Overlap Chart provided once again by The Independant Recording Network, you’ll notice that nearly all of the instruments share the same fundamental frequencies. Most of the sonic energy happens between 140 Hz and 6000 Hz. you’ll remember that this is roughly the same range where our ears naturally amplify sound.

The combination of energy and amplification leads to bad things sonically. When there’s just too much going on, we interpret it with terms like “harshness” and “tinniness” and “mud.” This buildup is normally addressed by competent engineers but you add an extra layer of variables when you factor in the sonic color of the in-ear. If you are listening to a monitor with extra boosts in these frequencies, you may be prone to hearing more issues in the range.

Keep your ears open now that you know what to listen for. Speaking of which, next week we’ll talk about ear training exercises so you can get even more out of your listening experiences.

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)