I have a few other questions:

1) What are attack, decay and transient? I think I understand the concepts in theory, but I don't think I have a practical understanding and I don't know what they sound like when I'm listening. Are there examples (like YouTube?) of what each sounds like?

2) What is (generally speaking) the greatest dynamic range of music? And how is that range measured? Is it measured equally above and below an average loudness (0dB?), so, say, -20dB and +20dB for a total of 40dB? Is dynamic range a measure of all sound that can be considered part of the music, or does it include the noise floor?...

3) What is noise floor exactly? I imagine that an easily audible one might be a hiss or a hum, but how else does it manifest itself? Where does it come from? Is there a difference between a recording's noise floor and that of a piece of equipment?

4) And finally (for now), what are the different measurements and thresholds that must be passed in order for a piece of equipment/media to be considered audibly transparent? Jitter, signal-to-noise ratio, distotrion... What else, and at what point can we no longer distinguish a difference for each?

It could quite easily take a book to answer your questions because many of the terms you've asked about are either vague to start with or have somewhat different meanings in different contexts. For this reason, some of my answers are somewhat different to the answers you've already received:

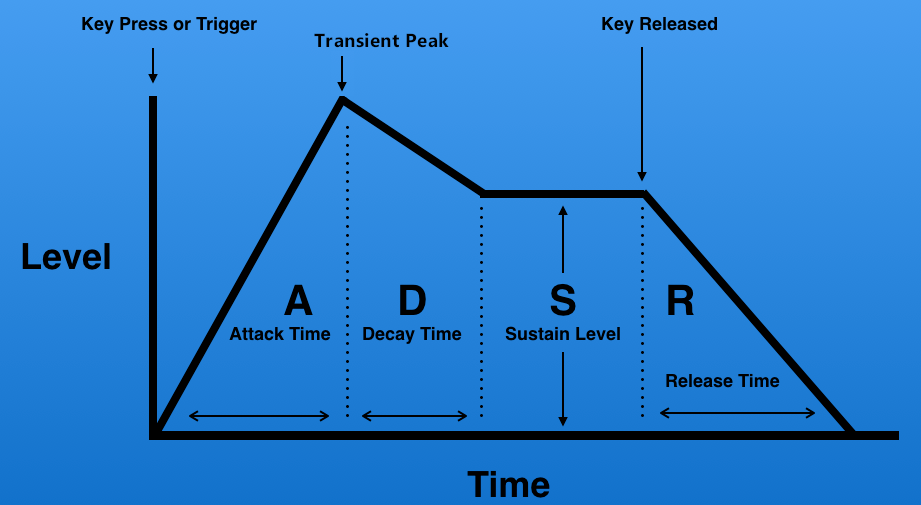

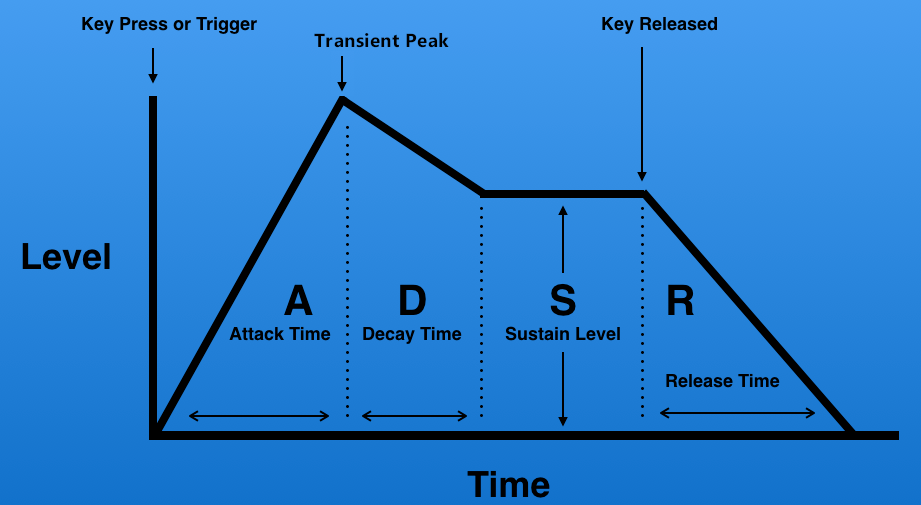

1. Attack is the initial phase of the production of a sound. For example: A finger plucking a string, a bow scraping across a string, the impact of stick/beater on a drum head, the start of the vibrations in the lips for a brass instrument or vocal chords when singing. Typically, this attack phase will last until the transient peak is reached, which can occur just a few tens of micro-secs after the beginning of the attack phase (in the case of some percussion instruments) or take several tens of milli-secs. Once that transient peak is reached, the sound/note will Decay (the amplitude will reduce) to the "Hold" (or "Sustain") phase, after which we enter the Release phase: This is the phase where the note stops being played and fades to silence. In some cases, the sustain phase is extremely short or non-existant, the decay phase and the release phase are essentially the same thing. This is typical of percussion instruments though not all, the marimba and the snare drum can be exceptions (when "rolled"). All these phases together are called the "Envelope" (and often abbreviated ADSR) and can vary enormously in duration, even in the case of a single strike on a perc instrument. The claves for example have very little resonance, no sustain phase and the entire envelope lasts just a couple of milli-secs, while the Tam Tam for example can last over 2 mins. This diagram might help you to visualise:

In some cases the release phase can start with a transient, typically when the note is "damped", using the tongue in the case of wind/brass instruments or the fingers/hand in the case of perc instruments like the timpani or triangle. Please also note that this ADSR envelope came into being with the invention of synthesizers, as all these phases could be created (synthesized) independently, however, many acoustic musicians don't really use it or use it differently. For example, "Attack" will often refer to both the Attack and Decay phases together, the Sustain phase is the same but the Release phase can often be referred to as the Decay.

If you have a simple audio editor, it's pretty easy to zoom in, isolate these phases and listen to them but particularly in the case of the A and D phases, listening to them in isolation often won't tell you much (even what instrument it is).

2. The "greatest dynamic range of music" is "pp" (pianissimo) to "ff" (fortissimo) but it isn't measured, it's judged. Pianissimo can have a wide range of different actual amplitude levels, even with same instrument and musician, depending on the acoustics of the performance venue. Dynamic range in the context of recording is the peak level relative to the noise floor (see #3). It's measured in dB but is usually somewhat subjective, as it's typically difficult to judge exactly at what point a note/sound disappears into the noise floor and it's further complicated by the fact that we can sometimes discern notes/sounds even when they drop several dB below the noise floor. Extremely few music recordings have a dynamic range greater than about 60dB and most have a dynamic range less (or significantly less) than 50dB. In the case of audio equipment, dynamic range is typically the range between it's highest undistorted output level and it's self noise. However, this can be somewhat vague/misleading, as the self noise of analogue audio equipment is higher when it's reproducing a higher level output signal than when it's idle (not reproducing a signal). The are other contexts as well though, the dynamic range of digital audio formats for example.

3. Noise floor can be a confusing term because it can BOTH refer to a single specific thing AND an accumulation of different things. For example, the noise floor on a recording is a combination of a number of different noise floors: The noise floor (self/thermal noise) of the microphones and mic pre-amps, the noise floor the digital processing (accumulated dither or quantisation error), plus of course the noise floor of the recording venue, which itself is a combination of different noise sources: External noise entering the recording venue, the noise made by the audience and/or musicians moving and breathing, the noise of air conditioning etc., and even potentially the noise that air itself makes (due to Brownian Motion). Almost always, there's a big difference between these various noise floors which comprise the recording noise floor. For example, the noise floor from the digital processing will almost always be two or more orders of magnitude less than the noise floor of the recording venue but there can be exceptions and in the case of analogue tape, the generational noise can easily become the dominant contributor to the recording noise floor, same with mics/mic pre-amps under certain conditions. The noise floor when reproducing recordings includes even more noise floor contributions: To start with, we obviously have the noise floor of the recording itself but in addition, we've also got the cumulative noise floor of all the bits of kit in the reproduction system (DAC, amp, speakers/HPs) and of course the noise floor of the listening environment, which like the recording venue noise floor is itself a combination of noise sources.

4. In practice, it's really only noise and distortion because all the potential artefacts/flaws produce either one, the other or both. For example, random jitter causes noise, while non-random jitter can create individual frequency spikes (which is a distortion of the original frequency content). For a piece of equipment to be considered "transparent", it's noise/distortion must be inaudible (at reasonable playback levels). Unfortunately, the audibility of noise and distortion varies according to the situation. For example, -40dB of noise will be inaudible in a loud, dense section of music but easily audible in a quiet, sparse section of music (if the noise floor of the listening environment is not higher) or, an audible amount of distortion at 3kHz might be inaudible at 60Hz. The only way to be sure of what is audible (and therefore not "transparent") is a DBT of that particular type of noise or distortion. In published scientific threshold studies, test conditions and signals are typically employed to highlight/exacerbate a particular artefact, which provides a good level of confidence that the observed threshold will not be exceeded under normal listening conditions. For example, some published studies have shown that jitter of just 2-3 nano-secs can be audible with specifically designed test signals but under laboratory conditions the lowest jitter demonstrated to be audible with actual music recordings was about 200 nano-secs.

Despite my apparently completely vague answer, we can make some generalisations, just be aware it's not a hard and fast rule, there can be (and are) exceptions. Assuming reasonable playback levels:

Noise/Distortion higher than -40dB will probably be audible in some/many conditions (though certainly not all!).

Noise/Distortion between -40dB and -70dB is unlikely to be audible in many/most conditions.

Noise/Distortion between -70dB and about -90dB will generally be inaudible to virtually all consumers but might be audible under some very uncommon conditions, such as: Very loud (but still "reasonable") playback levels AND particularly sensitive or trained listening skills AND extremely good listening conditions (laboratory, high quality studio or accurate and very well sealed IEMs for example) AND certain specific music recordings. It's very unlikely that noise/distortion lower than about -80dB would ever be audible to any consumer.

Noise/Distortion lower than about -90dB we can pretty safely say will never be audible. But, "pretty safely say" does not necessarily mean "say with absolute scientific certainty", although it comes pretty close

G